Empowerment for Diverse Abilities

Before beginning my role as Assistant Professor in Singapore, I established an art studio for disabled adults at Keswick Multi-Care Center in Baltimore, Maryland. The idea came unexpectedly during a visit to the medical center to deliver sketches for a mural commissioned by a nurse. When I arrived, I saw dozens of residents slumped in their wheelchairs in the hallways, seemingly forgotten. The sight was heartbreaking—how could people sit there for hours, doing nothing?

The next day, I returned with clay in hand. I moved ten wheelchairs into a circle on the porch and handed each person a ball of clay. Together, we began with simple hand-building techniques, creating pinch pots. As time went on, those pots transformed into animals, and a program began to take shape.

Word spread, and soon the facility’s management asked if I would like a part-time position with health insurance. For an artist, it was an ideal opportunity, combining creative work with meaningful and direct impact.

Realizing that a simple theme, such as “What does home mean to you?” could inspire powerful stories from individuals in wheelchairs, I envisioned an exhibition that would amplify their voices. Through the stories woven into their artwork, the exhibition became more than just a collection of beautiful pieces—it offered a glimpse into how people experience the concept of home when they are away from their personal spaces.

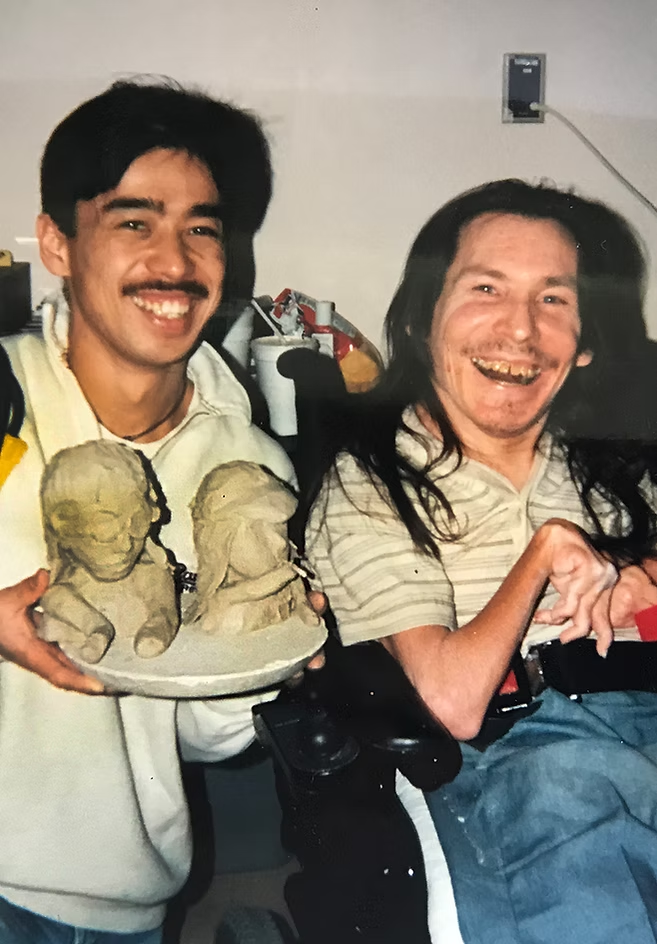

Robert, a resident of the Keswick Multicare Center alongside artist Hiro Kashima after sculpting David Bowie and John Lennon.

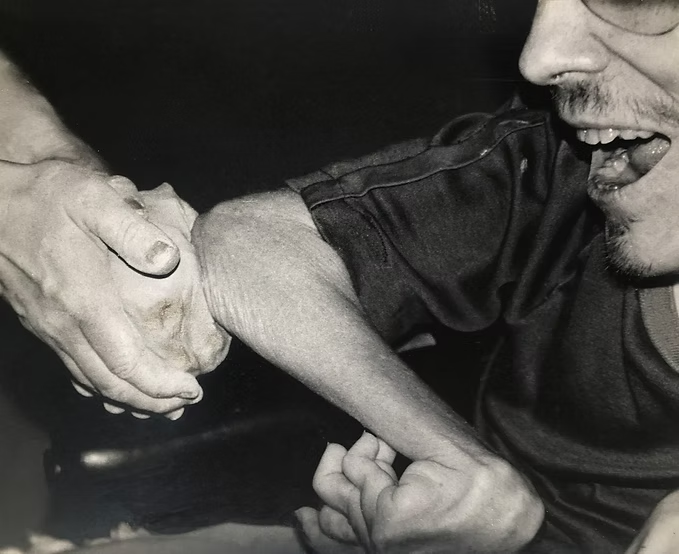

Robert making pots by me pushing the clay and him pushing his elbow into the clay.

Everyone Can Create.

The stories not only brought meaning to the work but also garnered publicity for Keswick Multi-Care Center. This visibility led to increased funding, enabling the hiring of another artist and the purchase of additional equipment and materials. A textile artist joined the team, and together, we sourced equipment from closed textile programs, expanding the studio’s capabilities and enriching its offerings.

My philosophy was simple: Everyone Can Create. No matter the condition of their body, everyone has the capacity to express themselves through art. The heart of this philosophy lay in autonomy; the decision-making process that defines the artwork as uniquely theirs. As long as the artist is the one making the decisions, the work belongs to them. We adapted to each individual’s abilities, exploring how they could engage with the materials of their choice. If their physical limitations prevented them from executing their vision, I became their artistic tool. Guided by their direction, I — or someone on our team, would bring their ideas to life, ensuring that every piece remained a true reflection of the artist’s intent.

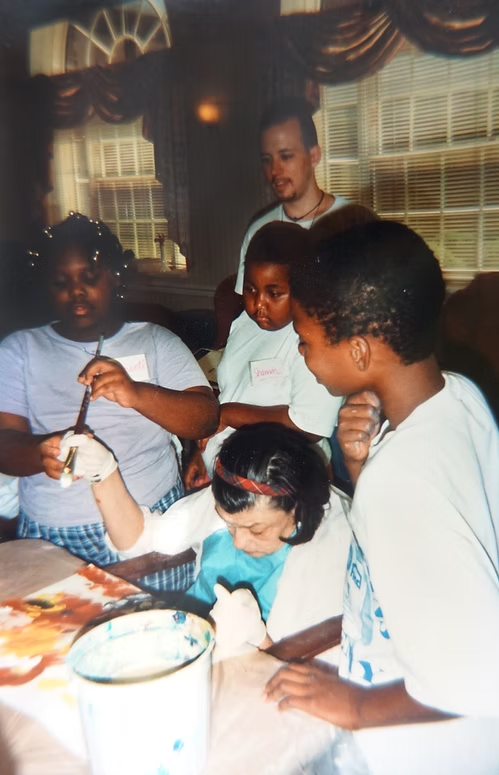

Residents of the Keswick Multi-Care Center engaging in clay work.

Intergenerational Exchange

Everyone required one-on-one assistance to create their artwork. Nearby, a local homeless shelter primarily served African American families during the early 1990s. Inspired by this, I conceived and secured funding for an intergenerational volunteer exchange program. Teenagers from the shelter provided one-on-one assistance to disabled adults, who designed their own artwork. Keswick supported the program by providing meals and snacks.

The process was collaborative: the adults communicated their vision for the artwork—what they wanted to create and how it should look—while the teenagers helped bring it to life. They worked together to determine what the adults’ bodies were capable of and stepped in to assist where physical limitations arose.

This experience highlighted how power can be both relative and situational. In this case, able-bodied Black teenagers were assisting disabled Caucasian adults. To me, this juxtaposition served as a poignant symbol of social and historical reconciliation—a process that has yet to be achieved in the USA.

The volunteers assisting a resident of the Care Center, Marylou.

The Potter’s Wheel

I was able to hire a potter to come once a week. He would assist the clients in making on the potter’s wheel or the clients would draw the pot shape they wanted. He would throw the pot on the wheel much larger. Then it was their job to glaze and fire the pot.

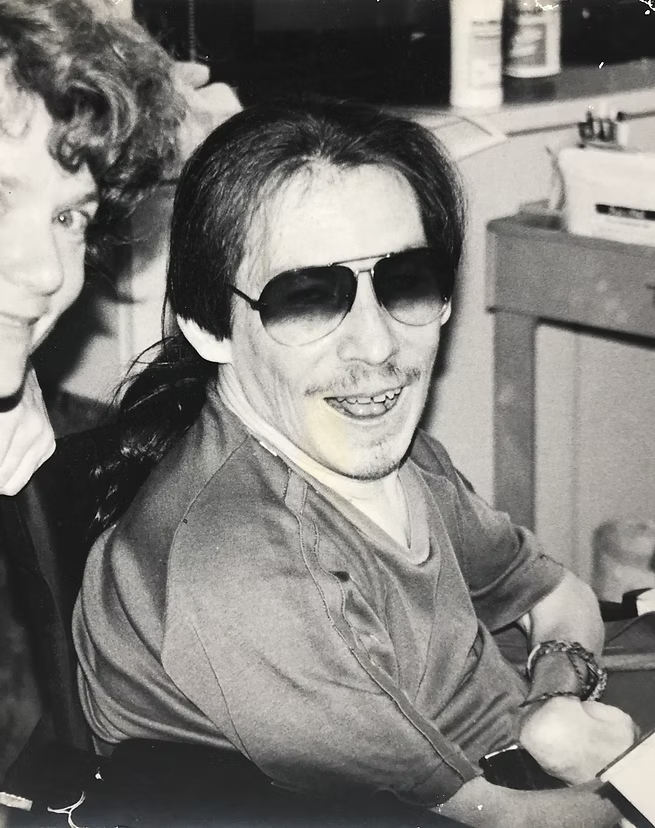

Robert’s Transformation through Clay

When I first met Robert at Keswick, he was completely withdrawn, always sitting alone in his wheelchair. Communication seemed impossible—he would only spell out words using his right pinky finger on the keyboard in front of him. Before I arrived, staff told me he would repeatedly type the same profane phrase, “F*** YOU,” over and over, directing it at everyone around him.

One day, after the group session had ended and the hallway had quieted, I noticed Robert sitting by himself. I approached him and asked if he wanted to create something with clay. Placing a block of clay in front of him, I introduced him to a wooden sculpting tool with looped blades on either end, designed to cut and shape the material. Carefully, I lodged the tool into his hand, he began to carve.

As the clay transformed under his touch, something shifted. The next day, Robert arrived at the studio, tool in hand, ready to join the group. His presence caught everyone’s attention, and they asked in surprise, “What is he doing with that tool?”

From that day forward, Robert became a daily fixture in the studio. His creativity flourished, and he emerged as one of the most imaginative and prolific artists in the program.

Robert with Joan.

The Textile Program

Our fibers program was a center of creativity. It began with the acquisition of looms from local universities that had, unfortunately, cancelled their programs due to budget cuts. These looms became the foundation for a thriving community of women and men where weaving, knitting, and crochet flourished.

Dyeing was another cornerstone of the program. We sourced standard silk T-shirts and dresses and introduced a unique twist by mixing a thickener into the dyes. Participants transformed these garments into wearable works of art, creating abstract, expressive designs directly on the fabric with a brush.

Interestingly, many clients hesitated to paint on traditional canvases. Their notions of “good art” were rooted in realism, and without the technical skills to achieve that, they shied away from trying. However, when the same abstract techniques with a brush and glazes or dyes were applied to large pots, T-shirts, or dresses, the work was embraced—its purpose as a functional or decorative item broke down the barriers of self-doubt.

This approach not only nurtured artistic expression while giving participants the confidence to see the beauty and value in their unique hand-work.