ISEAS Finland

In 2017, Katja Juhola, the Director of the International Socially Engaged Art Symposium (ISEAS), invited me to participate in a ten-day Socially Engaged Art Symposium in Raasepori, Finland. My role was to collaborate as an artist with Finnish artist Jan Jämsén and a community of women living with disabilities in a state-assisted program called Kårkulla.

Beyond providing Jan’s Facebook and email contact, there were no specific guidelines on how our collaboration should unfold. To gain insight into his artistic practice, I decided to interview him. During our conversation, one aspect stood out—Jan’s work is deeply rooted in Nordic shamanism, particularly hypnotic shamanic drumming, which serves as both inspiration and methodology in his artistic process. Intrigued, I asked him to send me recordings of these drumming sessions.

Sensory Collaboration

This sparked an idea. I decided to incorporate the shamanic drumming into my teaching, bridging my students in Singapore with the women in Kårkulla through a shared sensory and artistic experience. Both groups would listen to the recordings and create visual responses. For my students, this would be a unique opportunity to collaborate with women with Down syndrome—an experience that could challenge their perceptions of communication and artistic expression.

Jan also shared a video of the Finnish landscape, narrating the history of shamanic practices and the role of drumming in his work. To prepare my students for this exploration, I took them to a local exhibition at the Singapore National Gallery featuring Yayoi Kusama. Kusama’s work is an intuitive response to personal emotions, yet it also makes bold political statements. Her immersive, obsessive visual language disrupts space and structure, something I hoped would encourage my students to embrace their own unfiltered responses to the drumming.

Singapore’s culture is highly structured, where young people’s lives are often planned meticulously by their parents from an early age. There is a strong emphasis on doing things a certain way. In contrast, my experience has taught me that artistic interpretation thrives in ambiguity—where meaning shifts depending on context and intention.

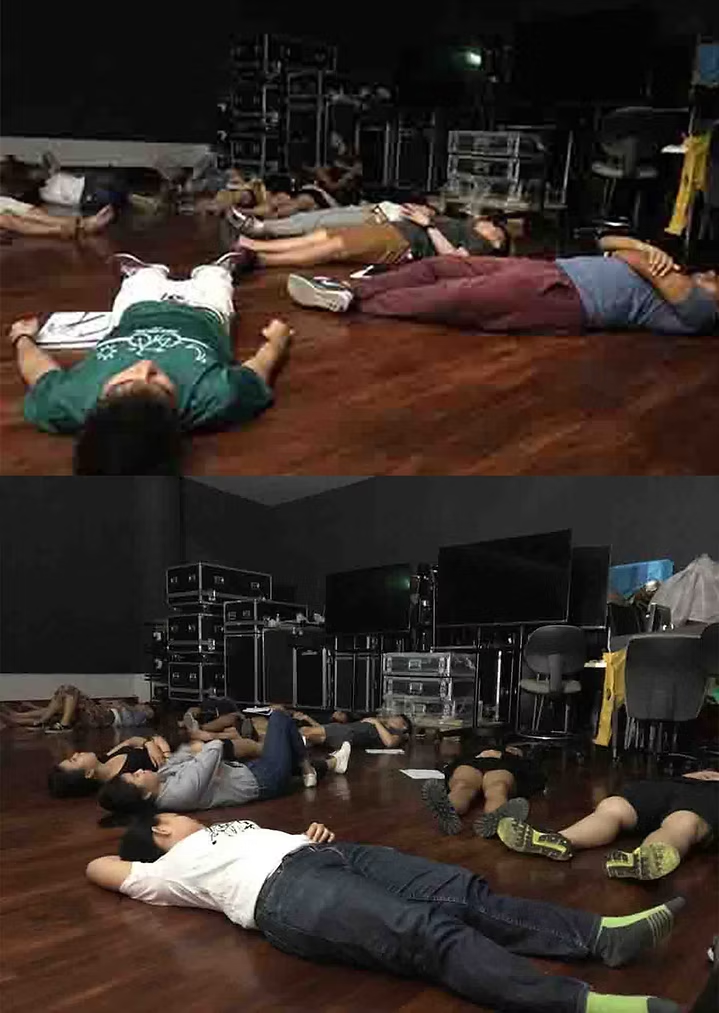

In the workshop, students listened intently to the shamanic drumming in a darkened room, allowing themselves to enter a subconscious, meditative state. They then recorded their experiences in writing before moving to their easels, transforming their visions into paintings.

Paintings from the women on show in Finland.

Responses

NTU Students

“This is the first time we did something without a plan.” Many students noted how uncomfortable they were working on an open-ended piece of artwork, or doing anything without a target outcome. They described how “in Singapore there is only one way to do something…” They discussed how restricted their lives are and that they almost never follow only their instincts.

Women in Finland

The women listened to the drumming and immediately began to paint. Many painted with their whole bodies moving to the rhythm of the drumming. It was as if their subconscious took over. They could connect immediately, making a relationship with the music, the color and the mark-making. Several of the women had Down syndrome but I didn’t ask questions as to their conditions we were involved in the moment.

Women in Finland working on their paintings after listening to the drumming.

Finale

For the finale, both groups met virtually through a dynamic sharing session on SKYPE. The women from Kärkulla were eager and confident describing their process, suddenly speaking English. Jan and I had no idea many of these were bi-lingual! They moved to the front of the plasma screen, excited, enthusiastic to tell the story of what they were thinking and feeling while making the artworks. They were actually elbowing each other! The students were shy and not sure what to say. Many of their paintings used dark colors unlike the uplifting colorful paintings by the women, not that this is better, but it is something the students brought up as a difference. Everyone was amazed at what we could learn from each other.

The Women’s response to the students was that of thrilled, being very aware during the Skype call that they the community classified as disabled, were teaching the students. The women were the ones leading the conversation. They felt very empowered being aware that they were teaching students in Singapore!

Conclusion

The experience revealed profound contrasts in artistic approach, cultural conditioning, and self-expression. The students, initially hesitant in the absence of structure, became deeply reflective about their own constraints. They recognized the confidence and spontaneity of the women from Kårkulla, leading to an unexpected shift in perspective—one of admiration and self-questioning.

For the women, the exchange was equally transformative. The realization that they were guiding university students, rather than being on the receiving end of instruction, instilled a sense of empowerment. Their natural ease in creative expression, uninhibited by external expectations, became a source of inspiration for the students.

The paintings from this experience will travel to three exhibitions in Finland.