Kayan & Big Ear People

This work represents an interdisciplinary collaboration between an myself, who is an artist and an ethnographic tourism researcher from Chiang Mai University, Thailand. As an artist, I am creating engagement with the ethnic community by painting their portraits and hiring local people as models. This is a means to create opportunities for the research team to observe and engage with the community in new ways and broaden the number of community members we engage with.

How it is that an ethnographic researcher conducts research in an ethnic community? The challenge lies in engaging as an outsider, without causing disruption. Gaining trust and confidence within such a community requires patience, and often years of consistent presence. Initially, a researcher might spend time in public spaces, waiting for community members to approach them. However, the practical constraints of research funding and university responsibilities make this slow, immersive approach difficult to sustain. An artist, on the other hand, can create interaction through creative engagement, quickly breaking barriers and building trust.

This creative research took place among the Long-Neck Kayan people in Huay Pu Keng Village, Northern Thailand. The Kayan, originally from Myanmar, sought refuge in Thailand due to conflict following Myanmar’s independence. For generations, they have lived as stateless communities along the Thai-Myanmar border in Mae Hong Son Province, approximately a seven-hour drive from Chiang Mai City. While often referred to as “Long-Neck Karen,” they prefer to be called Kayan, a name that literally means “long neck.”

Traditionally, only girls born on a Wednesday under a full moon were required to wear the brass neck rings (Phone Myint Oo, Mai and Regional, 2018). However, life as refugees in Thailand has altered this practice. Agriculture alone is insufficient to sustain the Kayan economically, making tourism their primary source of income. Visitors pay an entrance fee to the village and often pay additionally to take photographs of the women wearing the iconic brass coils.

These coils serve both as a marker of beauty and a means of economic survival (Phone Myint Oo, Mai and Regional, 2018). Therefore I wasn’t sure if due to necessity of economic survival in the tourism environment more women wore the neck rings today. When I asked the Kayan women wearing the rings told me no. However they also told me that with the rings a woman is much more desirable to men as a bride. The women are facing the tourist each day making money. While waiting for tourists dressed in traditional dress she is weaving on her front porch with her weavings displayed for sale. The men come in from the fields at the end of the day and she has dinner prepared for him. I’m sure that being the “bread winner” gives the women agency but I cannot say specifically in what ways because I wasn’t able to investigate this deep enough. The women could speak some English too. The men I painted could not speak English. This must also give the women agency but again I cannot say in what ways.

Despite their cultural significance, the rings cause physical discomfort. Women wear them not only around their necks but also just below their knees. Ma Peng, a Kayan woman, shared with me that the rings around her knees cause pain every day, regardless of how many years she has worn them. While the rings appear to elongate the neck, they do not actually stretch it. Instead, the weight of the brass pushes down on the collar bones and upper body, giving the illusion of a longer neck. The permanent rings are heavy, causing friction against the skin, and over time, the neck muscles atrophy beyond repair Phone Myint Oo, Mai and Regional, Mai. (2018) .Commoditization of culture in an ethnic community : the ‘long-necked’ Kayan (Padaung) in Mae Hong Son, Thailand. Chiang Mai, Thailand: Chiang Mai University Press.

Methodology I used as an Artist Collaborate in this Ethnographic Space

Before my arrival, the tourism researcher had already been visiting the village. He had established a connection with Ma Pang, a particularly entrepreneurial Kayan woman, who willingly and immediately took control of managing my work. Ma Pang had learned English from interacting with tourists, never having attended formal English classes. She sells her weavings and earns money by engaging with visitors, often posing for photographs, similar to how she initially interacted with me. However, as we worked together, our relationship evolved into a warm friendship.

Enroute to Kayan Village

The first morning I travelled by boat across a river to reach the Kayan village I must say I was a bit stressed. I only hoped I had all the materials I needed. With no way to get anything once across the river, the Kayan village being located on the other side I did not want to waste a day. I proposed to Ma Peng to painting a series of portraits of people in the village, compensating them for their time as my model in one-hour sessions. Artists customarily pay their models. Why should this be any different here? I did not offer an amount for the hourly wage. I opened this for Ma Peng to decide. This arrangement created an intriguing economic and social dynamic: While the villager sits and is paid, a reversal of the common stereotype in which the White person is the one being paid for little physical exertion. Here, the White woman, was working intensely to create a painting of the villager. The attention of the White person and the villagers who gather around is on the villager. The Colonial stereotype is that the White person does not give intense personal attention to the ethnic villager. The local people observed me concentrating, striving to capture their likeness within the short time frame. The intense heat made me sweat, further equalizing our positions. We shared the same space, and I felt their respect as they witnessed my effort. Showing-up and working has real meaning.

Each wooden structured home has a store front display of the women of the house’s weavings and other ethnic looking objects that are from Thailand but not originating from the Kayan village. I saw the competition between each other’s homes but I didn’t feel a malice from the women towards each other. This was demonstrated through their constant sharing and assisting to each other’s needs. While it is hot year round the homes are open air which circulates air but one can hear everything in each other homes.

What is Painting a Portrait

The act of portraiture creates a unique relationship between artist and sitter. The artist stares, and the sitter stares back. The artist’s gaze is not casual but deliberate, scanning the face and body, tracing contours again and again (Schuster & Kelly, 2019). This way of seeing is unlike ordinary sight, it is almost tactile, akin to the way a massage therapist’s touch makes one aware of their body in a new way. Often, we did not share a common language, yet through this prolonged exchange of looking, a relationship was forged. When I have been in an ethnic community 2 weeks or a month making portraits the community of women has always embraced me into their social circle. We relate as women surviving on our own. They realize I’m single, depending upon myself and even though they are married, they often times feel as if they are depending upon themselves because of the instability of their economic situation. They know my circumstance is different from theirs, yet we have commonality. I feel strongly that if I introduced myself as having a husband who has a corporate job that supports me, they would be happy for me but it would put a barrier between us. I’m also dressed to paint and work in the heat. I think if I walked around in branded clothes it would fulfil a stereotype of Caucasian people. I remember my first visit to Indonesia in the 1980’s. I was asked with confusion, “Why aren’t you fat?” “Is your father fat?” They related fat to wealth and here I was …what? A poor White person!

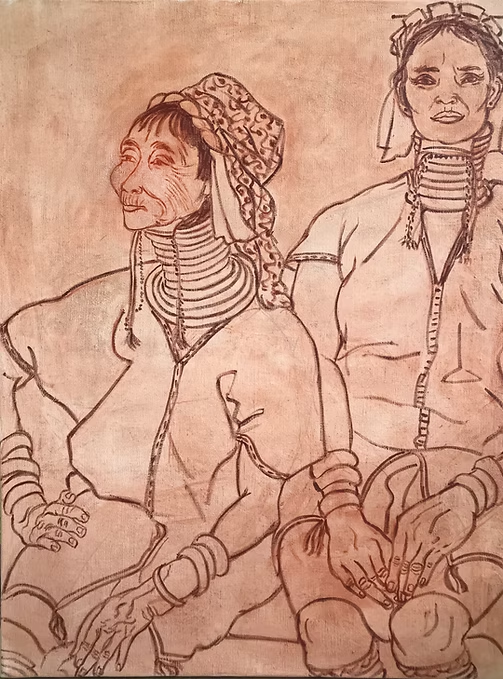

Ma Pang agreed to organized the models. I paid her a fee to make us lunch on and off. Basically, Ma Pang had me paint most of her extended family, keeping the money in the family. She also had me paint the oldest woman in the village Ma Cle three times to give her a chance to make money, demonstrating her awareness of how my desire to paint can serve well as a commodity and her empathy to do what she can for others with particular needs. I found this older woman, Ma Cle very smart and entrepreneurial. When I observed a group of tourists walking through the village, Ma Cle immediately grabbed her guitar and began to play music and sing fully dressed in traditional ware with her especially long set of knee rings attracting the tourists to come to her home-front tourist stall and possibly pass over the others. The immediacy with which she prepared herself, suggests a conscious “performance” of identity tailored for the external tourist audience. One might question the authenticity of this experience but I do not. In our predominantly capitalistic world we all have our “performance” at a job or however we market our skills. She is using the tools she has available to her, her culture. This is survival in a Capitalist society. Below is a very short clip of Ma Cle’s performance for tourists. You can also get a glimpse of how she organizes her store-front home.

I thought Ma Cle was in her eighties but although she looked quite aged she is only in her sixties. My misjudgement of her age to such a degree suggests that the physical toll of her life has affected her appearance.

I observed a deep pride in the Kayan heritage, even as it is presented in a way that aligns with tourist expectations. To be prepared for tourists at any minute, Ma Cle and Ma Peng’s houses were always in order and impeccably presentable.

A typical front of one of the Kayan houses displaying tourist ware.

Materials, Heat and Language Barriers

The paintings I created were actually drawings on canvas, made with a brush and oil paint. I was quite nervous because I struggled with the materials, and the heat—at least 32°C (90°F)—made it even more challenging. I don’t like to draw with a pencil or pen. I prefer drawing with a brush. I use the canvas because it can be rolled and transported easily without damage unlike paper. I sew the edges of the canvas and put rivets across the top side so that the work can be hung like a blanket on the wall leaving out all need for wood frames and stretching of the canvas. By using burnt sienna and turpentine, I rub the entire surface of the canvas initially to create a warm sienna tone all over. This way when I want to change a line during the process I simple wipe with a rag. I had depended upon a Thai friend of the researcher for the turpentine. As soon as I opened the bottle, I knew it wasn’t turpentine—the odor was much stronger. I had no idea what it was, but after coming all this way to the village, I felt I had to use it anyway. It was not only a paint thinner. I had cloth rags with me, but given the strong smell, I didn’t want to tone the canvas near Ma Peng or anyone else, so I moved away from the house. When I rubbed the thinner and sienna onto the canvas, the substance lifted some of the primer, which I could see on the cloth—a serious problem. The substance immediately dried into the primer even as some of the primer was on my rag therefore the sienna tone didn’t spread evenly. The tone wasn’t evenly smooth there were now dark and light patches. This you can observe in the photos of the first paintings. I finally found a hardware store on my own in town and use google translate into Thai to ask for turpentine and got the correct product. No one knew I was struggling, but for me it was a complete panic.

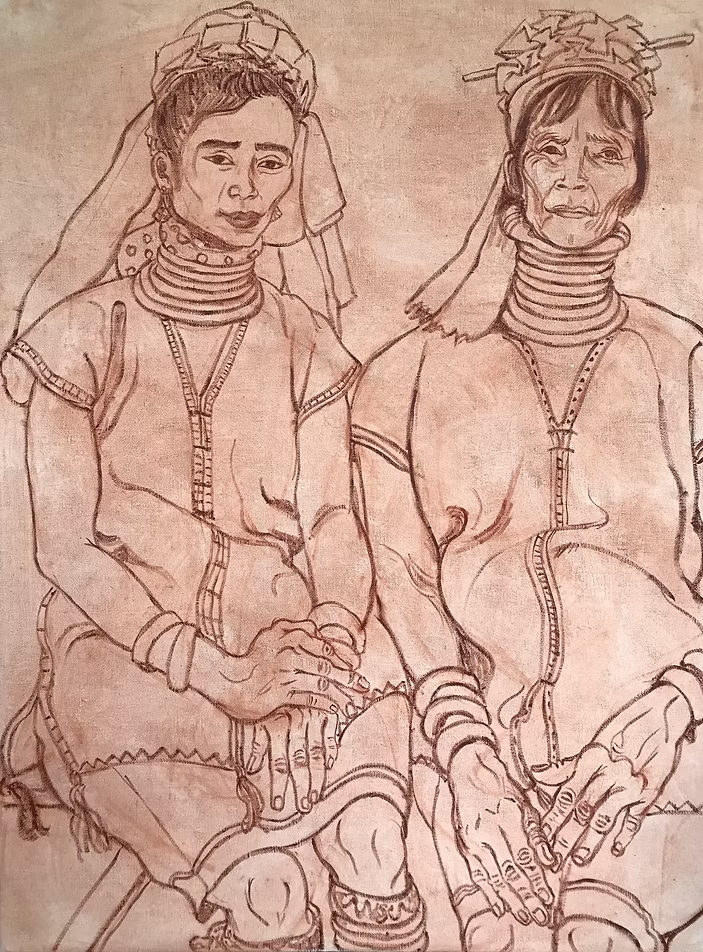

Two Kayan Women

Mae Hong Son Province, Thailand 2022

Oil paint on linen canvas (102cm x 84cm)

Ma Cle and Ma Peng’s Sister

Mae Hong Son Province, Thailand 2022

Oil paint on linen canvas (102cm x 84cm)

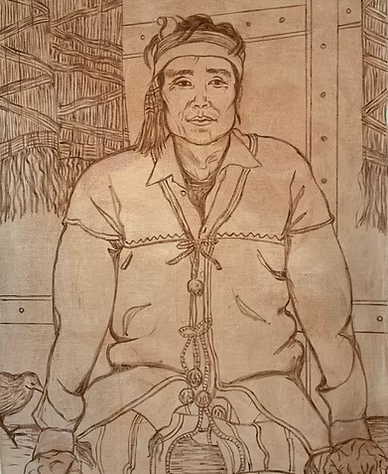

Ma Peng’s Husband

Mae Hong Son Province, Thailand 2022

Oil paint on linen canvas (102cm x 84cm)

Painting is a very Intimate Process, disrupting power structures

One day in the late afternoon husbands came into the village from working in the fields. I was painting a meticulously dressed woman in a colorful traditional dress and headdress and neck rings. A crowd surround us. The particular woman posing with was the wife of one of the husbands. When he saw her he burst out laughing. The volume of the whole crowd rose and laughter was everywhere. My model was smiling ear to ear, so I presumed she enjoyed the attention. I could not know exactly what they were saying but I distinctly had the impression that perhaps he had not seen her in the spotlight since their wedding day? I was very happy his response was laughter and not being uncomfortable or resistance to this shift in dynamics, seeing all the attention of the village on her. Portrait painting has a unique way of temporarily transforming social roles and often times placing women in roles of attention and admiration shifting social status. The portrait raises the status of the sitter, and perhaps shifts how the sitter sees themselves in relation to the Kayan community. It is not hard to notice the status and agency the women who is organizing the models has when everyone wants to be one who makes the money for sitting an hour. Every ethnic community I have worked in making portraits, the role of organizer created agency, yet the other women seemed very accommodating, waiting their turn. I felt no aggression towards her. If anything I saw the women being super supportive of her. This process of an artistic engagement oriented method exposes subtle power structures and community values in ways that traditional research might not capture.

Ma Peng’s Brother-in-law

Mae Hong Son Province, Thailand 2022

Oil paint on linen canvas (102cm x 84cm)

I painted two women together who are not wearing neck rings. A woman who could speak English came over to me and asked if I would paint a woman without the neck rings. She was bold to overt Ma Peng’s control of my schedule I thought. I told her “Yes.” She responded “Oh I thought you would not want to paint a woman without rings.” Of course I consider women without the rings important as all members of the community are. The painting I did of these two women together came out stiff. I feel the same way about the Brother-in-law painting above. Compare the brother-in-law to Ma Peng’s husband. There is a lightness and flow to Ma Peng’s husband. Usually less is more. Sometimes it’s the pose they take. I don’t dictate the pose. Perhaps I should take control over it. I have always thought of it as fate and maybe I don’t like telling the models how to sit. I cannot find an image of the painting of the two women without rings. Maybe it’s because I subconsciously left it out not being pleased with it. Presently, I am professor of Practice at teaching position at Woxsen University in India. My paintings are in storage in the USA therefore at the moment I cannot shoot the original but I will as soon as I have an opportunity.

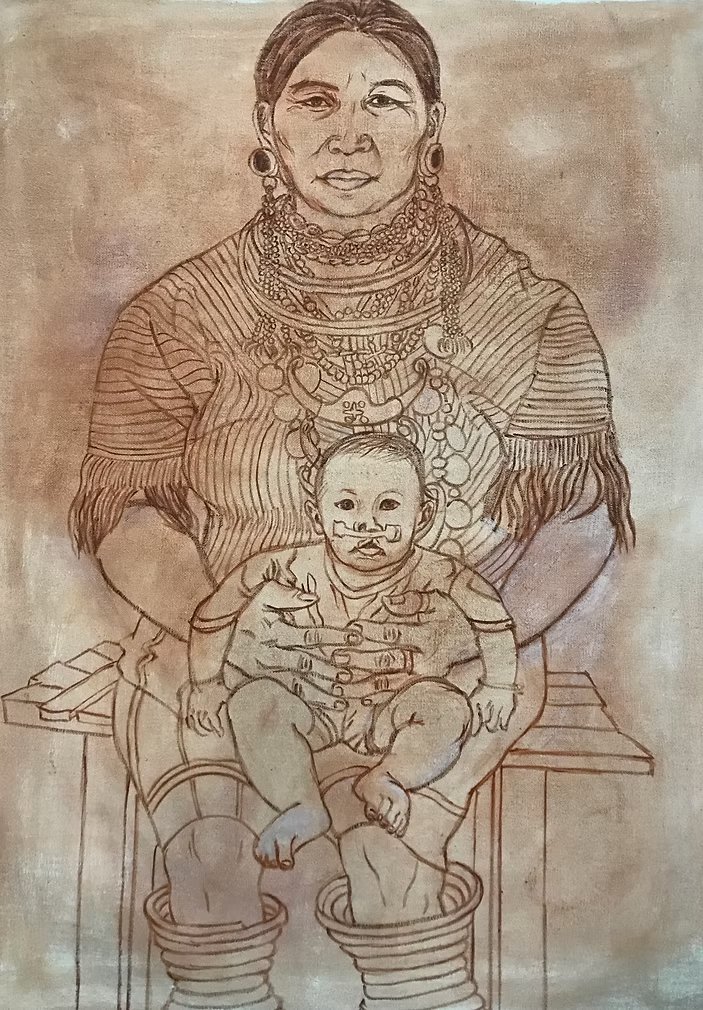

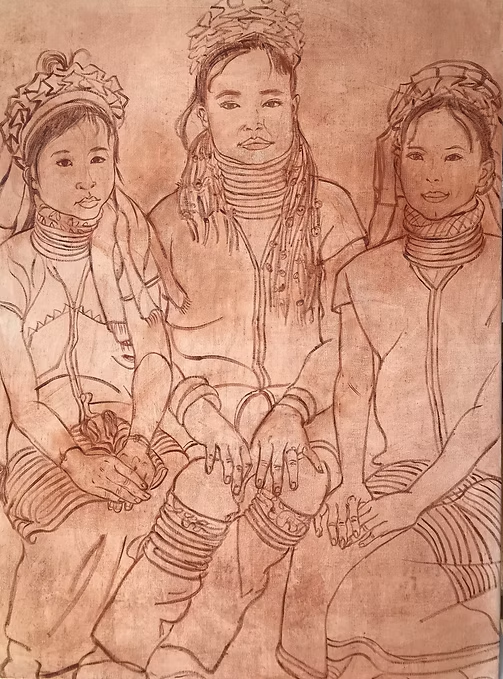

Other Ethnic Groups living Together within the Kayan Village

A small minority in the Kayan Village were from other ethnic groups having fled Myanmar. Among them were the Big Ear and Red Karen communities. I did not hang out with the women in either tribe. Ma Peng took me over to their house for me to paint a specific older woman although there were many younger people. When my hour was up she came and got me returning me to her house where I often ate lunch. My Peng kept control over my schedule. I think it is generous and considerate for Ma Peng to have me paint the older women who may not be able to earn as much money as others in the village. My paintings capture the ear plugs in the lobe of the ears. One grandmother of the Big Ear community, came to pose holding her grandson who she was caring for during the day while her daughter worked. I told her the baby posed too. The infant has a clef palette. When I inquired the mother told me that they have a scheduled surgery to repair it. Although unnecessary, I paid the baby the same hourly wage. It felt fair. I don’t know exactly how she felt but she gladly took the money. These small gestures I feel build trust.

No one was with me as an interpreter during these painting session. At some point Ma Peng no longer accompanied me during the sessions. She would drop me off at the sitters house. I assumed she trusted me and felt comfortable with leaving, giving her time to carry out her chores and being available for tourists. Other times she would have the sitter come to pose in front of her or her family member’s house attracting the attention of tourists.

Big Ear Grandmother with grandson

Mae Hong Son Province, Thailand 2022

Oil paint on linen canvas (102cm x 84cm)

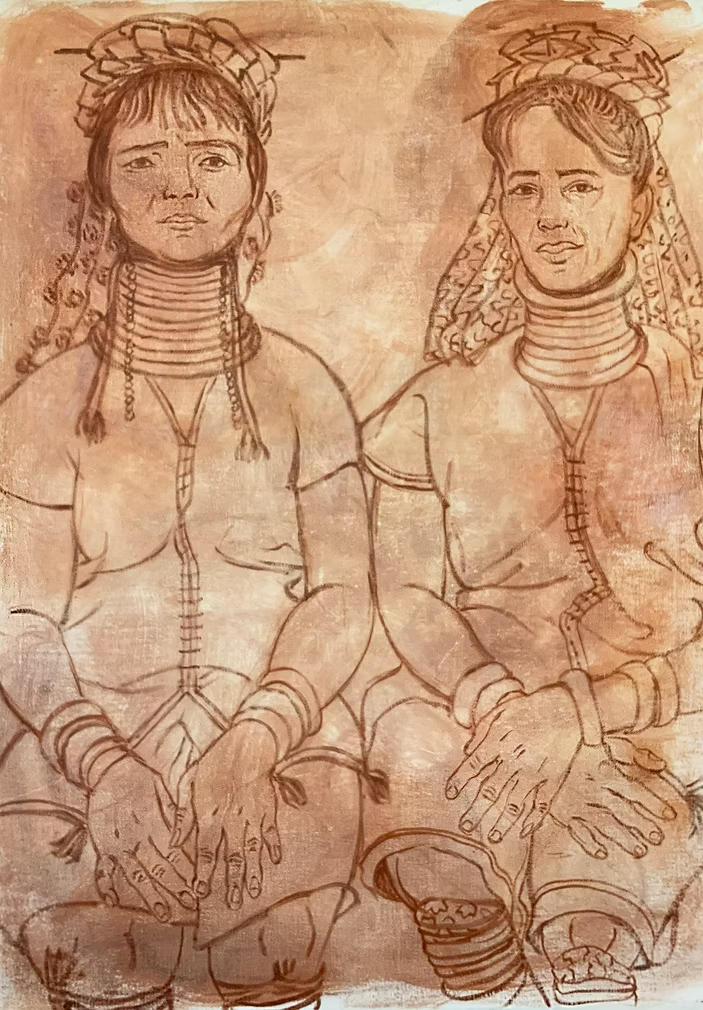

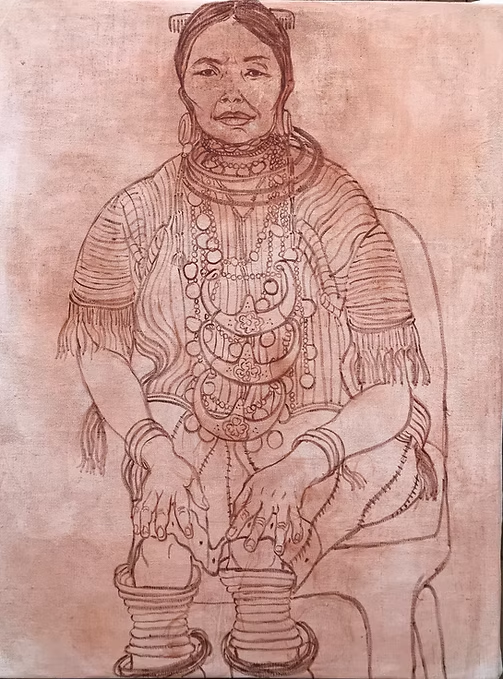

Big Ear Women

Mae Hong Son Province, Thailand 2022

Oil paint on linen canvas (102cm x 84cm)

Shared Female Experiences

I became close to several of the women. I absolutely feel strongly that every male ethnographer needs to bring a women with them. Women are not going to open-up to a male about how they feel personally about love, marriage and the intimate contours of their lives. I asked a woman who was not wearing the neck coils why she isn’t wearing them. She doesn’t want to. This led to a discussion of how this impacted her options to get married. I learned from the women that a man doesn’t want to marry a women without the neck coils because of her lack of economic opportunity the neck coils attract from tourists. What does her life look like without a husband? She wasn’t bothered at all because she said she always has a home with her family. I saw her often creating weavings with other women in her family sisters and sister-in-law’s.

Another woman and I talked about arranged marriages. She told me a story of loving a man her parents would not allow her to marry. She ended up marrying the man her parents chose. As a result the man she loved left the village. To this day she does not want her daughters having the same experience. She will not impose her views on her daughters. They will marry who they choose. I asked her what her wedding night was like if she did not have feelings for him. She told me of five or six members of the village coming to their new home with alcohol after the wedding. Everyone was drinking into the night. Finally everyone left leaving the new couple alone. She said they went to separate rooms and slept. It took about a week for them to finally sleep together. When I asked her if she loves him now? She explained, he is a good man. She fixes his meals takes care of the house and does his laundry if that is love then she loves him.

At one point Ma Peng asked me to wear the traditional dress. I have never been to any ethnic village or community in Asia where the women have not wanted me to wear their traditional dress. It’s a way of sharing connection and intimacy through clothing, adornment and hair styling. I feel to not go along is rejecting their traditions and rejecting who they are. It’s an extension of hospitality and affection and maybe curiosity rather than cultural appropriation. There are pictures of me in traditional dress on the internet and often I have been criticized by Western peers who have never been to Asia for cultural appropriation.

The day Ma Peng wanted to dress me in traditional dress. We were sharing female experiences but I was also aware of the fact that this too would attract attention to her home-front store, and what is wrong with that? If I can help her in any way I would. The Thai ethnographer who I was there with got very angry with me for putting on the traditional dress. I can understand him being concerned about cultural sensitivities shaped by his concerns over power dynamics, representation or historical exploitation but he assumed it was my initiative to do so without inquiry. This I feel showed his dismissal of the possible agency of the Kayan women, never considering that they are who initiated this gesture. It tells me he looks at himself as a protector of the Kayan community instead of one that allows for reciprocal exchange and space for the voices of the women involved. This experience brought up the reoccurring issues of scholars having ethical concerns while those in the culture have their own perspectives which do not align with the outsiders critique. By him not accepting that I would be relating to the women in this way through their initiation, he is asserting intellectual and social authority over me, possibly of male scholar and female artist. He being the arbitrator of ethical conduct. His academic role granting him authority over interpreting cultural interactions rather than my direct engagement. I was dually happy that the women embraced me socially, that we could connect, and that I could give them a tiny bit of economic relief when they posed or if that used me to show-off to tourists.

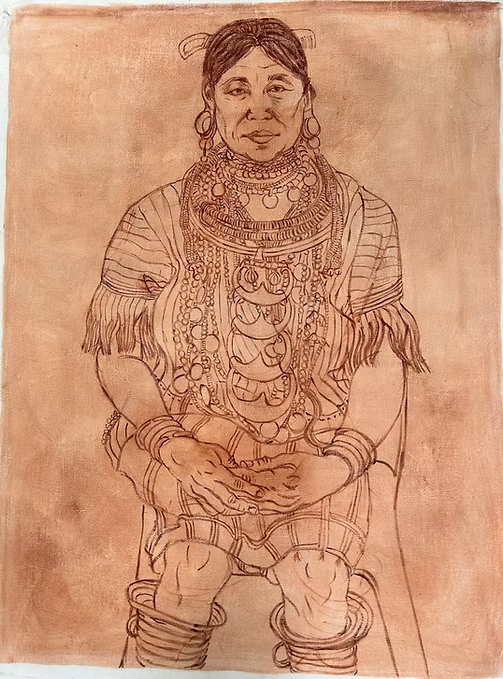

The Kayan Women

Mae Hong Son Province, Thailand 2022

Oil paint on linen canvas (102cm x 84cm)

Facilitating a Drawing Workshop for Children

I can’t say this was a successful workshop for collecting information. The children were laughing and drawing, so it was enjoyable for them. However I wanted to ask more uncomfortable questions as prompts for their drawings. I am aware of how there is a prominent cultural norm throughout Asia where people don’t talk openly about uncomfortable subjects or directly address solving problems. Therefore, I waited too long into the session to give a tougher question to the children. They were obviously restless. The question I was able to pose was “what do you fear the most?” The drawings were made quickly, I think because they were anxious to run off as a group. Every child drew a natural disaster. such as the strength of the wind or the river rising and flooding their home or their home floating down the river. The children told me through an interpreter what the drawings were about. However, I don’t know if because they were in a rush a few people thought of the natural disaster and the rest followed which is a possibility with children. All and all I thought the response to this one question was very interesting and led to me ask questions that led to being told of past recent floods and damaging wind storms. I had not realized how vulnerable the village was seated along a river while home are built with very impermanent methods.

A drawing of the wind blowing the roof of the house off by one of the kids.

Here is a very simple drawing of the river rising with homes floating on top of the water by the kids.